For the first time in decades, the Renaissance Center faces a real possibility of losing its title as the tallest building in Detroit. But if local and world history is any guide, its challenger must first survive a dream-wrecking national recession that could be just around the corner.

Businessman Dan Gilbert’s real estate firm plans to break ground in downtown Detroitthis fall on a 1.3 million-square-foot building packed with office, retail and event space and a 68-floor residential tower that would soar 800 feet into the air.

That tower, to be topped with an observatory and “skydeck,” would outstretch the Renaissance Center, whose highest tower at 727 feet has held the city’s — and Michigan’s — height record since 1977.

Gilbert’s firm plans to construct the $909-million building on the site of the old J.L. Hudson department store, a block-long building that closed in 1983 and was imploded in 1998. The land has since been vacant aside from an underground parking garage.

Yet before Gilbert’s Hudson site building can break records and wow visitors with over-the-skyline views, it may have to ride out the so-called “skyscraper curse.” That is the theory that construction of tallest buildings is a signal of an overheating economy that is nearing its peak, with a downturn fast approaching.

The skyscraper curse was first put forth in 1999 by a British economist who noted that the Empire State Building was announced on the eve of the Great Depression, the Willis Tower (formerly Sears Tower) opened the first year of the 1973-75 recession, and the Petronas Towers in Malaysia opened in the wake of the 1997 Asian financial crisis.

“Is there truth to the skyscraper curse? I would say yes,” said Lucas Engelhardt, an associate professor at Kent State University who co-authored a journal article last year about the theory. “Especially if you see a cluster of these buildings being planned, that’s a pretty good sign there’s something coming.”

In Detroit, proposals for the city’s tallest buildings — and other large projects — have been repeatedly scuttled by economic downturns.

Examples include plans for a second and a third Fisher building in New Center that were proposed in the booming 1920s but cancelled amid the Depression. The unbuilt centerpiece of this trio was to have been a massive 60-story structure flanked by two smaller buildings. Only one of the smaller buildings — today’s 30-story Fisher Building — actually happened.

And a much-larger sibling to downtown Detroit’s Book Tower was proposed on the eve of the Depression and ultimately canceled. That unbuilt 81-story tower was to have soared about 900 feet and would still be the city’s tallest building.

More recently, a 2006 plan championed by Detroit’s then-Mayor Kwame Kilpatrick to build 480 condos on the riverfront, called @water Lofts, unraveled in the Great Recession.

Under some interpretations of the skyscraper curse, proposals for tallest buildings are harbingers for recessions because they can demonstrate behaviors that tend to signal the high point of an economic expansion, such as heated speculation, easy lending and eagerness to take on debt. By the time such projects get under way or have finished, the economy may be contracting.

“It’s a pretty good indicator that you’re nearing the peak,” Engelhardt said.

But no one can know for sure when the next recession will actually hit.

Charles Ballard, an economics professor at Michigan State University, said he believes it is “certainly unlikely” that a recession will arrive in the next six months, barring extreme events such as the outbreak of war.

He was also skeptical that Gilbert’s Hudson site blueprints offer any sort of premonition for the direction of the nation’s economy.

“I think this expansion has lasted as long as it has because this one has been slow and somewhat steady,” Ballard said. “We know that a recession is almost certain to come eventually. I hope we can get at least a few more years before it happens.”

Dramatic upswing

Gilbert’s Hudson site plan does coincide with a dramatic upswing in the once-moribund downtown Detroit real estate market for which the founder and chairman of Quicken Loans, a Forbes list billionaire, is largely responsible.

Gilbert’s real estate firm, Bedrock, is now downtown’s largest landlord and has done extensive renovations to many of the 90-plus buildings it owns or controls.

Once awash in vacancies, downtown’s vacancy rate for Class A office space is now a low 7% and asking rents were up to $24.36 per square foot in the second quarter, according to data from the Newmark Knight Frank real estate service firm. Six years ago, when there was less move-in-ready space available, the vacancy for all types of office space in downtown was 36%.

Still, it’s an open question whether downtown could successfully absorb all the new space that would come with the planned Hudson site building, as well as Gilbert’s other proposed downtown building projects. But optimists, including Gilbert himself, contend that demand in downtown is so strong that the coming building boom represents fundamental growth — not irrational exuberance.

“There is no indication that the energy that is now in downtown will not continue to grow,” said John Mogk, a longtime professor of development law at Wayne State University. Gilbert’s organization, he said, “has a better finger on the pulse than anyone ever had because they own all the buildings. So their projections should be far more accurate than any developer who ever attempted to do something significant in Detroit.”

Jared Fleisher, vice president of government affairs for Quicken Loans and the family of companies, said the coming construction is not a sign of an overheating real estate market. He noted how downtown Detroit hasn’t seen any new office buildings go up in more than a decade.

“It’s not as though we’ve been building and building,” Fleisher said. “There has been a tremendous unmet demand.”

Gilbert detailed his latest plans for the Hudson site during a news conference last month inside Detroit’s Book Tower, a once-opulent downtown building that fell into disrepair and was bought two years ago by Bedrock.

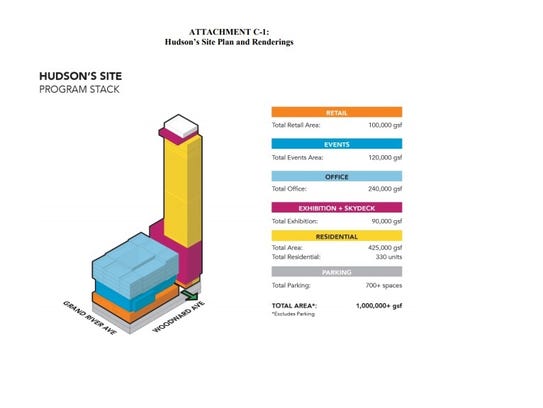

The building at 1208 Woodward Ave. would have more than 300,000 square feet of new office space, 100,000 square feet of retail, food and beverage space, and about 167,000 square feet of exhibition space. Then there’s the pièce de résistance: the 68-floor residential tower containing 330 apartments.

“These have been wildly popular in the handful of cities that have them,” Gilbert said, an apparent reference to the newer skyline-piercing residential towers in cities such as New York that are typically billed as luxury properties.

Gilbert went on to describe how the rectangular tower will be topped with an observatory.

“It will allow people to get up there and feel proud of their city and region,” he said.

A graphic showing the different sections of the planned Hudson site building (Photo: Bedrock)

Most of the tower’s residences will be market-rate apartments with asking rents that have yet to be announced. However, at least five apartments are required by city ordinance to be set aside as income-restricted affordable units. Those tenants would likely be selected by a lottery.

The Hudson site tower could very well become one of Detroit’s most desirable addresses.

“The fact that it will be the tallest building in the region will sell 20% of the apartments,” said Jim Bieri, principal at Detroit-based Stokas Bieri Real Estate.

Gap financing

Although demand and leasing rates have been rising in downtown, development experts say there is still a gap between the construction costs for new highrises and the rent levels in Detroit that could support such developments.

So financing for the Hudson site project will hinge on a mix of public subsidies and development incentives, including a new Transformational Brownfield initiative signed into state law this June to support developments on blighted sites that could have a “transformational impact” on a local economy.

The initiative and related programs will provide roughly $100 million of the project’s $909 million costs, according to Bedrock. That development incentive is not a grant, but rather a reimbursement to Gilbert’s real estate firm of portions of various future taxes at the site.

The total reimbursement will ultimately be $195.7 million and will include state sales and income taxes for construction activities; 30 years of property taxes; and, for 20 years, up to 50% of future state income taxes generated from the new jobs as well as the new residents inside the completed building.

The project will also receive incentives from three other programs. Those amounts were not immediately available Friday.

The property tax capture was specially designed to not capture any city of Detroit taxes or taxes for Detroit schools.

Bedrock’s application for the incentives estimates that the building would house 1,007 new full-time office jobs with salaries around $85,000. The retail, restaurant, event and exhibition spaces are expected to support another 626 jobs.

Build it, they’ll come

Highrise developers generally must pre-lease at least half of their planned building before breaking ground, at the insistence of their lenders, said developer Peter Allen, a real estate lecturer at the University of Michigan’s Ross School of Business.

Gilbert’s Bedrock, however, is preparing to break ground for the Hudson site building by Dec. 1, even though it has yet to secure many tenants. Construction could take at least three years.

“We’re much more ‘If you build it, they will come,'” said Fleisher, the spokesman for Gilbert’s family of companies, noting the plummeting downtown vacancy rate. “It is that current vacancy rate that rationally leads to the confidence in making this investment in the future, even if signed (letters of intent) are not done yet.”

He added: “If everything we did in Detroit over the past seven years was dictated by lenders, we never would have gotten going. We’re trying to take this market to the next level — that means that we can’t be at the mercy of conservative lenders.”

For some, the next question after whether Gilbert can build and then fill his highrises is what happens throughout downtown once those new buildings open.

When the Renaissance Center arrived in the late 1970s, it flooded the market with leasable space and led to a surge in downtown vacancies as office tenants left older buildings, such as the Penobscot and First National Building, for the new tall glass tubes.

“It sucked out a lot of other buildings,” said Detroit historian Bill Worden. “A lot of people decided they wanted to be in the modern prestigious place, and it took a lot of time I think for the historic buildings to recover.”

But as Bedrock officials and others see it, an influx of new office space will be a net positive because downtown can then attract and accommodate businesses that aren’t yet here. Much of the currently available Class A office space is in small chunks and non-continuous. That isn’t attractive to big firms that may wish to come downtown.

“Right now we have no capacity to attract major companies and job creators to Detroit because we have no place to put them,” Fleisher said.

The ultimate boost for downtown would be landing Amazon’s planned second headquarters. Detroit is among dozens of cities vying for that prize, a $5-billion investment involving 50,000 new jobs. Gilbert is leading Detroit’s bid.

Allen, the U-M professor, said landing Amazon would make it easy for Gilbert to accomplish his planned buildings. Yet even without Amazon, he thinks the additional office space would be a valuable lure.

He noted how some companies have been leaving suburban campuses for urban environments, such as General Electric, which recently relocated its headquarters to Boston from Connecticut’s leafy Fairfield County.

“If Dan Gilbert doesn’t get Amazon, he will get somebody else,” Allen said, “or two or three firms that are in some ways even better than Amazon, because it will be a more diverse mix.”

As for skyscraper curses, Allen cautioned against relying too much on historical trends to forecast the future. He offered a local example.

“Who would have predicted five years ago that Detroit would now be so robust and recovering?,” he said. “So looking back and looking at what history would suggest —and I’m a history major by the way — is not a definite indication of what will happen this time.”